In previous posts, we discovered how being memory-aware improves performance.

The array-based BST was ~53% faster than its pointer-based counterpart, and we saw how garbage collection algorithms can spend 85% of their time stalled on memory accesses.

But, there’s a fundamental layer we need to explore the virtual memory. Every memory access in a program goes through virtual memory translation.

This blog post will try to explain:

- Why this layer exists?

- How it works?

What is virtual memory?

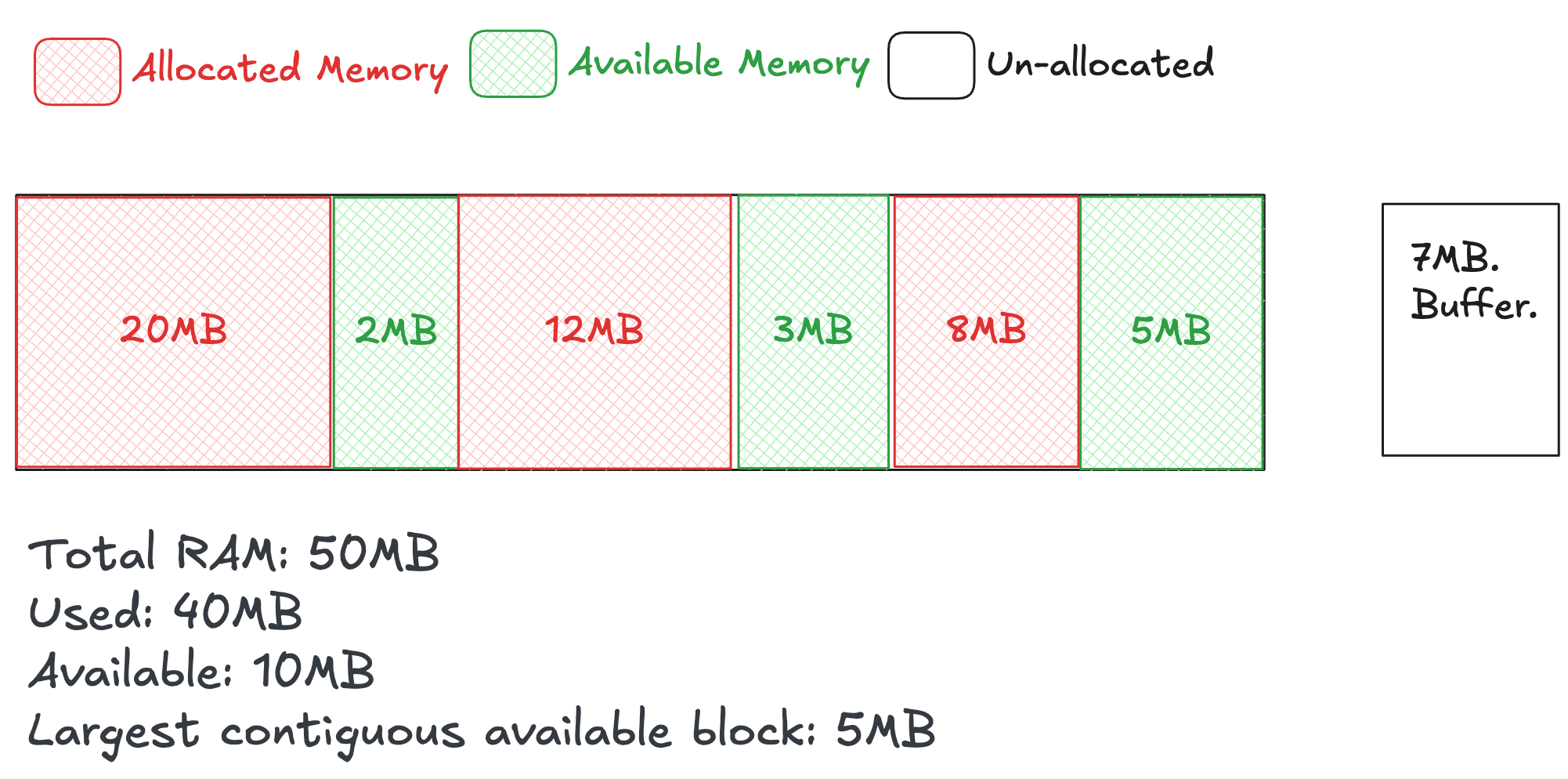

Processes in a system share the CPU and main memory with other processes. With sharing comes challenges. As demand for the CPU increases, processes slow down but, if too many processes need too much memory, then some of them will simply not be able to run. Memory is also vulnerable to corruption if some process writes to the memory used by another process that process might fail in some unpredictable fashion totally unrelated to the program logic.

Virtual memory is an abstraction layer interacting with hardware exceptions, hardware address translation (MMU), main memory, disk files, and kernel software that provides each process with a large, uniform, and private address.

Virtual memory provides three important capabilities.

Address Space

The address space is provided to each process, this makes each process think it is alone in the system. A virtual address space is implemented by the Memory Management Unit (MMU) of the CPU.

Efficiency

It uses main memory efficiently by treating it as a cache for an address space stored on disk, keeping only the active areas in main memory, and transferring data back and forth between disk and memory (I/O) as needed.

Without it, programs would be limited to physical RAM size with no ability to use disk as extended memory.

Simplifies memory management

It simplifies memory management by providing each process with a uniform address space.

Without it, programs would need to track and manage fragmented physical memory locations manually.

Process isolation

It protects the address space of each process from corruption by other processes.

Without it, programs would require cooperative memory management, making system crashes and security breaches inevitable.

How it works?

Let’s understand some of the key building blocks that make this abstraction possible.

Page

Page is usually a 4KB fixed-size contiguous block of memory within a process’s virtual address space. Pages exist for batching efficiency by creating manageable units for memory translation - instead of tracking millions of individual byte addresses, the system groups them into 4KB chunks and translates entire chunks at once. Pages map to the physical page frames through page tables. The page tables are used to resolve every virtual address into a physical address using the page table walk.

| |

This creates a slice of 10K integers. An int is of 8 bytes.

- Size: 10K * 8 bytes = 80KB

- Pages: 80KB / 4KB = 20 pages

- Virtual memory: 20 contiguous 4KB chunks in the address space

- Physical memory: 20 page frames scattered in RAM

- Page table: Maps each virtual page to its physical page frame

Allocating virtual memory (Linux)

The mmap() system call can be used to allocate virtual memory by memory mapping.

| |

The Linux kernel finds a contiguous, unused region in the address space of the application large enough to hold size bytes:

- Modifies the page table

- Creates the necessary virtual-memory management structures within the OS to make the user’s accesses to this are “legal” so that accesses won’t result in a segfault.

Segfault is a failure condition raised by the hardware. It is occurring when a program attempts to access memory it is not authorized.

If you’re coming from C, malloc is part of the memory-allocation interface in the C library while mmap is system call. The heap management code within malloc attempts to reuse freed memory whenever possible

and when necessary, malloc invokes mmap and other system calls to expand the size of user’s heap storage.

Address Translation Breakdown

Every memory access in the program triggers address translation. Some are expensive and some are cheap (cached). Let’s trace through a concrete example.

| |

Calculate virtual address

The data variable is a slice and Go’s slices are structs with three fields:

| |

For the sake of example I have arbitrarily chosen 0x5555_8000_0000 as the header pointer base address.

The element 42 offset is then 42 * 8 bytes = 336 bytes (0x150).

The virtual address is 0x5555_8000_0000 + 0x150 = 0x5555_8000_0150. Since offset 0x150 = 336 bytes < 4096 bytes (4KB page size) address of index 42 data is in the first page of the allocation.

Address Translation

| |

Page Table Walk (on TLB miss)

The page table walk is the process the CPU uses to translate a virtual address to a physical address when the TLB misses.

The page table walk requires walk through 4 levels where each level requires reading from main memory the final level gives physical page frame address. It is expensive because of these 4 memory accesses.

The page table walk is the “slow path” fallback when TLB cache misses. It’s what makes the virtual memory work, but at performance cost. This is why TLB hit rates are so critical, they avoid this expensive process.

Translation Lookaside Buffer (TLB)

The TLB stores recent virtual to physical translations and TLB hit is extremely fast (1-3) cycles.

TLB is a small extremely fast cache, modern CPUs provide multi-level TLB caches, just as for the other caches; the higher-level caches are larger and slower. The small size of the L1-TLB are fully associative, with an LRU eviction policy.

Influencing TLB performance

Larger page sizes help because more data fits per page requiring fewer translations but memory fragmentation in this case makes allocation difficult.

Additionally, we can try to explicitly prefetch TLB entries through software prefetch instructions, but it’s worth noting that it doesn’t directly operate on the TLB, but by speculatively bringing data into the cache, it can indirectly help mitigate TLB miss penalties by initiating page walks earlier and ensuring that page table entries are more likely to be in the TLB when needed.

Languages like C and C++ expose prefetch capabilities through compiler intrinsics. Go doesn’t expose these low-level prefetch intrinsics, but developers can achieve similar results by “touching” memory locations to force address translation and load TLB entries.

Go:

| |

TL;DR

Virtual memory solves process isolation and resource sharing. In order to solve these problems, it requires an abstraction layer that translates virtual addresses to physical addresses.

Pages are the fundamental unit of virtual memory translation they divide both virtual and physical memory into identical 4KB chunks. Each page holds 4KB of actual program data (variables, arrays, code, etc.). Their role is to be the atomic unit that gets mapped - the system doesn’t map individual bytes, it maps entire 4KB pages from virtual address space to physical page frames in RAM.

Address translation happens on every memory access and branches into two paths:

- The fast path (TLB hit in 1-3 cycles)

- The slow path (page table walk requiring 4 memory accesses at ~800+ cycles).

The performance of your program depends heavily on which path is taken.

Page tables are multi-level data structures that store which virtual page maps to which physical page frame. They’re organized in 4 levels because a single-level table would be too large - this hierarchy allows sparse representation but requires walking through multiple levels when the TLB misses.

TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer) is a small, fast cache that stores recent address calculation of page-to-page-frame mappings to avoid expensive page table walks. It’s the critical component that makes virtual memory perform well. Without it, every memory access would require the slow 800+ cycle page table walk.

The complete system trades translation overhead for the benefits of isolation and flexibility. Programs with good spatial locality stay on the fast path, while scattered memory access patterns frequently hit the slow path and suffer performance penalties.